We continue our exploration of the Armenian contemporary art scene. Previously, we described the challenges of developing a full-fledged Art market in Armenia. This time, we delve into the artistic re-interpretations of the post-Soviet heritage and Armenian contradictory cultural identity. Lava Media correspondent Catherine Chernova spoke with Gor Yengoyan – a contemporary artist and a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts – about a recent exhibition at :DDD Kunst Hause, on the post-Soviet and the Eastern art.

Catherine Chernova: Let’s start from the beginning: what’s going on in Armenian art education right now? What’s new in the Academy of Fine Arts, in particular?

Gor Yengoyan: Well, I studied at the Academy of Fine Arts myself, and now I teach there. Recently, we got a new rector, Vartan Azatyan, and he’s trying to upgrade and renew the art education. In this case, it’s important that the Armenian Art Academy is a post-Soviet institution, and it’s very similar to other institutions in the post-Soviet countries. Armenian Academy was founded in 1945, so firstly, one has to understand its original function, which is to produce professional artists who would work within the framework of Socialist Realism. For instance, we recently opened archives from the 1940s and 1950s, and there’s a canon in every detail – if you draw an athlete, or a workman, you draw a figure in a predetermined pose, which is already ideologically approved, and nothing can be changed.

Then, during the Khrushchev Thaw, the Academy began to move away from the canon it was originally built upon, and in doing so, the institution opened itself up to the modernist perspectives of the era. But at the same time, it also lost something important.

CC: You mean, its thorough character?

GY: More like its educational program. Whether we liked that program or not, it served as the foundation of institutional education. Today, in my own teaching practice, a crucial question is how things worked back then and how we can apply that experience now these days – where the so-called “academic-artistic” and “research-conceptual” components are meant to work together. That’s very interesting to me, because since 2003 I’ve been working with contemporary art, while still having those academic skills. I’m fascinated by the idea of working with these seemingly contradictory approaches as a unified whole. And that’s a question the Academy of Fine Arts itself is facing right now.

CC: You mean the contradiction between academic and contemporary conceptual art practices?

GY: Exactly. At first glance, they seem completely incompatible. But You know, I can spend forty minutes in the Centre Pompidou looking at [Christian] Boltanski’s installations, and then spend just as long contemplating a Bruegel painting. To me, they are based on the same artistic logic – just separated by time.

I always say: if someone is making contemporary art and dismisses everything else as outdated, or if they only praise Bruegel and Bosch and see no value in contemporary art – each way is to disregard the art itself. Honestly, I’m glad that I’m teaching from this place of understanding

CC: What do You teach?

GY: I teach comics. This practice is offering me a great opportunity to work with students over a long period just on a single project that includes both a conceptual research component and a production-based with its academic craftsmanship. So the academic and “modernist” traditions coexist within comics.

CC: But You also work with animation and curatorial practice, right?

GY: Yes, I work in animation. I used to work at the Armenfilm studio, back when it still existed. Now I’m an animation artist — I create storyboards and concept art. But I don’t curate much these days, although I used to organize quite a few projects, particularly at NPAK.

CC: Curating requires a specific kind of expertise, doesn’t it?

GY: Yes, You’re absolutely right. But since we don’t really have curatorial education in Armenia, artists often take on those responsibilities themselves. As an artist, I can organize an exhibition of artists whose work I relate to and understand – but that won’t be a professional curatorial approach. Because an artist is always an egoist; it’s hard for them to stick to ethical boundaries, because they also want to exhibit themselves. Teaching, on the other hand, is different – a teacher is expected to work, to discover, and to share the discoveries with students.

CC: As an artist, do You have a certain direction in Your artistic research? Do You define it in any way?

GY: I understand where that question comes from, but I prefer not to have a complete answer. Five or six years ago, I probably would’ve had one – back when I was working more strictly within the “modernist tradition.” But now things are different. I just want to focus on things that feel close to me, things I recognize. I’m not trying to look far away or to solve someone else’s problems. I’m looking at things right in front of me – at Armenian history, at the present day.

I think it’s really important right now – not to work separately with two traditions, the official Soviet one and a kind of “liberationist” tradition that emerged during the Khrushchev Thaw. Today, both of them are part of our inheritance, and so they form a new tradition woven out of contradictions. And this is relevant not only to me as an Armenian from Armenia; I think it’s a common post-Soviet phenomenon. And I’ve learned to live beyond that conflict of the two different traditions.

Выставка Small Things, :DDD Kunst Hause / Фото предоставлено Гором Енгояном

CC: So, the new tradition is a combination of conformism and non-conformism in art?

GY: No, that’s not what I mean. People are naturally inclined to take sides, to align themselves with something. But it’s much harder to see that there are no real binary oppositions – no pure black and white. For example, when we talk about “official” Soviet art, You and I might instinctively want to distance ourselves from its authoritarian nature. But within that tradition, there were people who sincerely believed in what they were doing, without being authoritarian themselves.

I have a significant example: as a student, I had a great professor – a staunch academic classicist, and of course, he didn’t like what I was doing. But we could have real debates and long conversations, because he was arguing reasonably, rather than just dismissing what he didn’t like.

Soviet academic education wasn’t just about the NKVD office; it also involved highly educated, competent people. That’s an important tradition we’re only now beginning to really engage with. Previously, those who aligned with “modernism” simply rejected that tradition – without studying it, without understanding the motivations behind it. And meanwhile, this Soviet academicism wasn’t even purely Soviet.

CC: Right, formally speaking, it’s the result of painters studying how color, light and volume work.

GY: Exactly. Here’s a simple example of working with color: I send a video installation to an exhibition in Hamburg, and I include a technical instruction, carefully describing what color the furniture around the screen should be – my goal is to make sure nothing in the display contrasts with the red color on the screen, that nothing distracts from the focal point. That’s color theory, which is artistic theory, which is academic theory. It’s really odd to deny that academic principles still function in contemporary art.

CC: You once said that this kind of denial is “stalinist” at its core.

GY: Yes. Thinking that the dissident rejection of conformist art is itself an example of a “Stalinist” attitude toward tradition – it’s a provocative thing. For someone, it’s even nonsense to suggest that Tarkovsky, for instance, could be seen as “Stalinist.” [Editor’s note: In artistic terms, this is an oxymoron, since director Andrei Tarkovsky worked definitely in opposition to the official artistic directives imposed during Stalin’s time.]

But think about what Stalin did – aside from the repressions – what did he do to culture? He shut down libraries, he edited the history.

CC: And he literally dictated how history should be handled, through articles in public press.

GY: Exactly. I’m not justifying that “modernist” phenomenon, and I’m certainly not criticizing Tarkovsky – I love rewatching Andrei Rublev, for example, because it’s a true masterpiece. But when I bring up “Stalinism,” it confuses, because people have always been afraid of it. When Armenian art historians started researching someone like Minas [Avetisyan], when they started promoting a national form of “modernism,” they wrote in articles that this art had absolutely nothing to do with Soviet academic heritage. And that action is also Stalinist in essence – because by method it’s editing history. It’s like claiming that the NEP never happened, that Lenin never existed, or that there was no tsar in the Russian Empire.

Another example: in the 1980s and ’90s, there was a post-Soviet art group called Third Floor – are You familiar with them?

CC: Yes, I am. They were quite remarkable.

GY: One of them, Ara Hovsepyan, was my drawing teacher. Back in the 1980s, he would say representing his peers: we’re cosmopolitans, we’re Western, we were the first to exhibit outside the USSR. But all of that is absolutely a Soviet phenomenon – exactly to claim that you’re completely detached from Soviet artistic tradition, while living there in USSR, owning a flat there, paying taxes there. That kind of denial itself is deeply Soviet.

CC: And what about now?

GY: Now we’re beginning to figure out what, exactly, the protest of the Thaw era was really against. I believe that this is the beginning of the true end of the Soviet Union – the end hasn’t happened yet, it’s only approaching. Its essence lies in acknowledging everything Soviet, in recognizing that it existed and that we’ve inherited it. Whether we like it or not. Both of those traditions – the official Soviet one and the anti-Soviet one from within the USSR – are equally part of our heritage. And by the way, that practice of denying tradition, which is essentially “Stalinist”, is also part of our tradition.

CC: So instead of linear development, we get complex, chaotic transformations.

GY: Everything’s mixed up. Even the post-World War II status quo is shifting.

CC: So what’s happening with Armenian art in this context?

GY: We’re still working within our own tradition, which is deeply rooted in both the post-Soviet and the Middle Eastern culture. Our local themes are incredibly important right now. We have this conversation in 2025 – the war in Karabakh has ended, the war between Russia and Ukraine continues, and there’s chaos everywhere. The post-WWII consensus, the global status quo, has collapsed. The context of global art is also shifting.

Personally, I am more interested now in working with the Middle East – not Europe, not Russia. But many Armenians forget that the closest metropolis to Yerevan isn’t Moscow or Paris – it’s Tehran, and a city of 15 million people, with a modern art museum, and thousands of art galleries. It’s a vast, wealthy city, the heir of the Persian Empire. And we forget that.

CC: The Islamic Revolution didn’t change anything?

GE: It changed a lot, of course, but it doesn’t mean that Iranian people don’t understand art any more. Just to acknowledge, today, 40% of the artists represented at major biennials in Arab countries are from Iran. And Iran has been Armenia’s neighbor for over 3,000 years. The Armenian language shares about 70% of its vocabulary with pre-Islamic Persian. There’s so much potential for our collaboration with Iran. Also about potential working with Turkey and Azerbaijan, at least in terms of contemporary art. I truly hope that these collaborations become possible in the near future. That’s very important to me. Because we are also people of the Middle East – we relate to each other on a different emotional level. Overall, Armenia is fascinating in spirit because it is both Middle Eastern and Soviet at the same time.

CC: And European also?

GE: That’s the dilemma: we’re Christians surrounded by Islamic states. Physically, emotionally – we’re more Middle Eastern. But in our aspirations, we lean toward Europe, we reach for Enlightenment ideals. It’s part of the Armenian tradition – to be Eastern in our everyday life, and Western in our ambitions. And on top of that, we also carry a Soviet past.

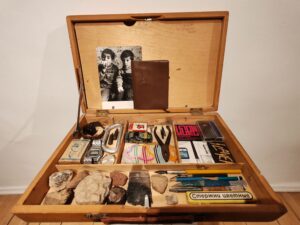

Do You remember that little suitcase from the exhibition at :DDD Kunst Hause

Выставка Small Things, :DDD Kunst Hause / Фото предоставлено Гором Енгояном

CC: Yes, and what’s curious is that it also feels very familiar to me, even though I didn’t experience the Soviet period at all – I just grew up surrounded by it. And it’s remarkable how long this radical divide between the Western and the Soviet persists, how hard it is to let go of the Iron Curtain, even though it fell 35 years ago.

GE: That’s a post-Soviet phenomenon – the contradiction between Western and Soviet traditions. And of course, it shapes our current tradition. And in Armenia, we also have Eastern traditions, which coexist in a fascinating way with both Soviet and Western ones. This is important to recognize. It’s connected to the real changes currently happening in Armenia – after the revolution, or even after the war of 2020.

The change is this: people started to realize that they live here, that our neighbors are not Russians, Americans, or Germans, but Turkey, Azerbaijan, Iran, and Georgia. And we have no other neighbors. The change is in beginning to notice the contradictions within our tradition, which turn out to be contradictions in themselves. We’ve started to see that. And when I say “we,” I mean myself as well.

CC: And what was going on before? What was the contemporary art scene before 2020 or 2018?

GE: There was a high level of polarization. That’s a very Soviet thing – you’re either a nomenklatura member or a dissident. Now, the relationship to tradition has changed, it’s no longer positive or negative – it’s become inevitable. In the past, a person either proclaimed themselves a supporter of European values and rejected tradition, or exalted the traditional. And then suddenly, you realize you’re the heir of both. And your tradition is to be contradictory. Unfortunately, that often means being uncomfortable with yourself, drowning in contradictions.

CC: And how does the Armenian viewer relate to this tradition of contradiction and to contemporary art over the past five or six years?

GE: That’s a very important question. I’ve noticed that as soon as an artist recognizes this contradiction, their works begin to resonate with everyone. And I really mean everyone – workers, taxi drivers, art critics. I saw this with Lusine Navasardyan’s exhibition, and even with my own exhibition at :DDD Kunst Haus. And I’m not used to this! I’m used to people not considering my work art, saying, “my grandmother could do that”; to knowledgeable defenders; to those who criticize something for being not leftist enough or too leftist – You know this. But here, everyone likes it – each for their own reasons. I show the work to different people, and each finds something interesting in it, because I don’t emphasize a singular position.

CC: And You work with small things?

GE: Yes, in fact, the recent exhibition at :DDD Kunst Haus is titled just that. I look down at my feet – I’m interested in small things.

CC: It’s interesting that You think in such broad categories, recognizing Your connection to different traditions, but You do it by looking down at Your feet – as far from generalization as possible.

GE: It’s also about the distribution of energy – it doesn’t matter if you’re an artist, a teacher, or a mathematician. If you reach for something huge, there’s a good chance you’ll only grasp it superficially, with arms not long enough. But if you work with a small thing, you’ll understand it much better. It could be something tactile or a craft you’ve been practicing for decades. A repetitive action, like in that work with the tally marks – that’s just personal time, without any pain.

CC: Speaking of pain. Big emotions are rarely well expressed through artistic means – so maybe it’s clearer and more honest to focus on what fits in your hands, so to speak. Not to talk about huge, complex feelings, but about how small things work. As if that might be more honest than trying to express big emotions through expressionist means.

GE: Exactly – big and small. Emotion is huge. But if we’re talking about honesty – honesty isn’t about not lying, because visual art is, in essence, a skillful lie. I’ve never thought about art in terms of honesty. The honest part isn’t about how truthful I am – for example, when I teach, I recommend softly shading something that sticks out or doesn’t work – that’s what artistic technique allows, that’s the very essence of artistic technique. Honesty is elsewhere – in whether you’re genuinely interested in the topic, in whether you overcome something while creating the work. And truly understanding what interests you. That’s another challenge, not an easy one to figure out.

CC: Especially within traditions that contradict one another.

GE: Yes, I suppose so.

Выставка Small Things, :DDD Kunst Hause / Фото предоставлено Гором Енгояном

Версию на русском читайте здесь